Review: The Spiritual Adventure of Henri Matisse by Charles Miller; The Illuminated Window by Virginia Chieffo Raguin

Two books exploring the spiritual and narrative possibilities of stone and glass, space and light

It was spring 1941, and at the Clinique du parc in Lyon the Dominican nurses had a nickname for their new patient. They called him ‘le ressuscité’ – the man raised from the dead. He was 71 years old. He had had two emergency operations on his intestines – followed by two blood clots, one in his heart and another on his lungs, both of which nearly killed him. Then his wounds became infected. He was finished, his doctors told each other. But they were wrong: Henri Matisse was not yet done. By the autumn he was painting again. “It’s like being given a second life,” he wrote to his son.

Between those perilous months and his death in 1954, Matisse would produce some of his most original and influential work. This included developing a découpage technique for his book, Jazz, which opposed pages of fluidly biomorphic shapes and voluptuous colours with monochrome handwritten texts. Among the texts was a long quote from a book that Matisse had by his bedside through the 1940s: the Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis, a late-medieval meditation on the Christian life. Matisse’s chosen texts came from the chapter on divine love; if nothing else, it indicated Matisse’s direction of travel.

Matisse had been raised in the Catholic church but left if far behind him in adult life: his children were baptised, but he made no effort to inculcate any faith in them. Unlike modernist contemporaries like Georges Rouault or Marc Chagall he had never accepted any commissions for work in new churches; his oeuvre is strikingly free from overtly Christian themes. But even while recuperating in Lyon his thoughts had turned to designing a Dominican chapel as an act of thanksgiving, and in the autumn of 1947 an opportunity came his way. It was he said, “a labour for which I was chosen… at the end of my journey”.

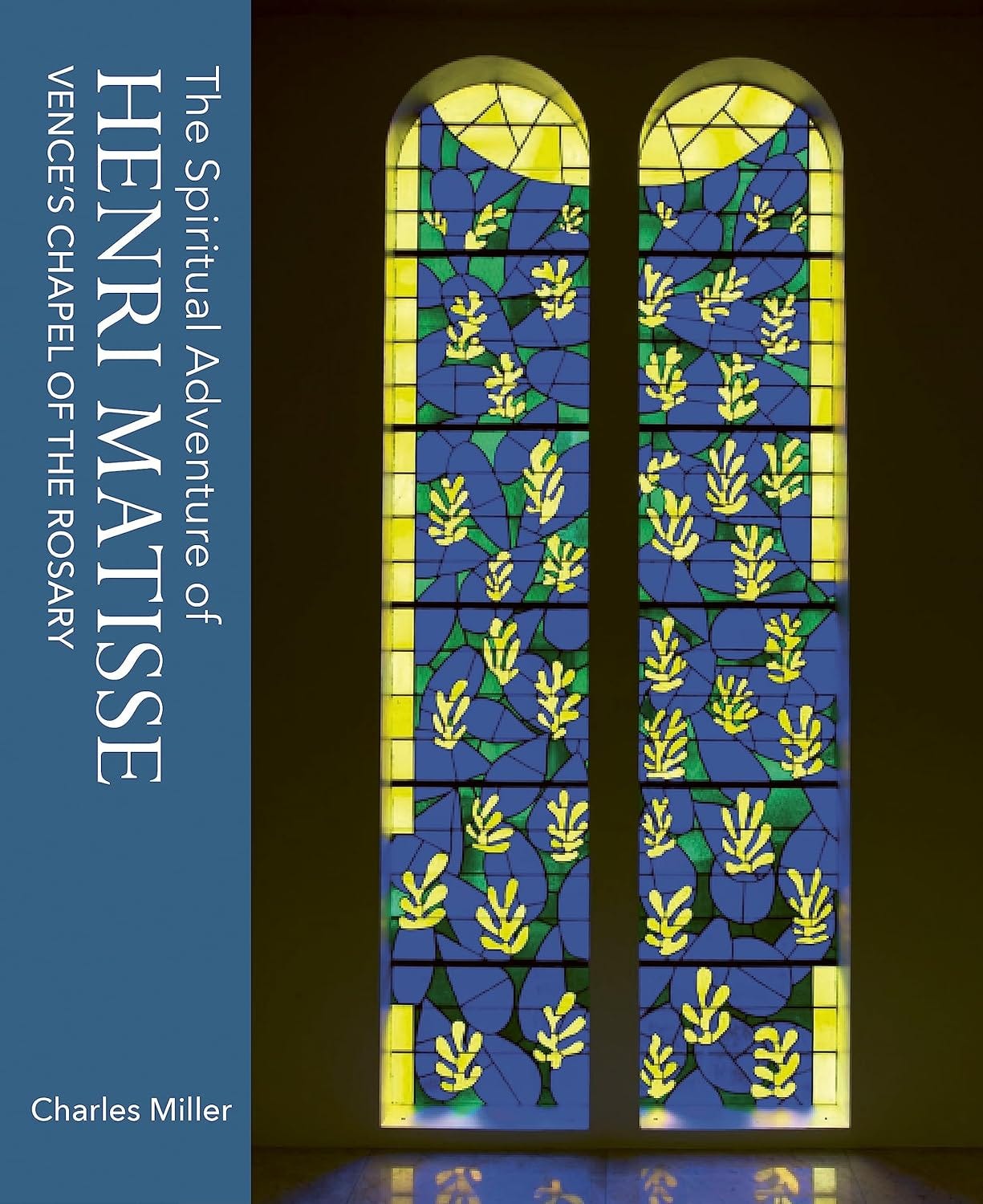

This labour – the creation of the Chapel of the Rosary in Vence – is the subject of Charles Miller’s The Spiritual Adventure of Henri Matisse, which is primarily an exploration of how the project, and the last years of Matisse’s life, were shaped by profound engagement with developments in 20th-century Catholic – and specifically Dominican – thought. It is, in Miller’s phrase, a study of “the synergy between theology and aesthetics”.

Matisse described the chapel as “the fruit of my whole working life”, but in Miller’s telling it was his most collaborative work. Central to the book are the dialogues, both epistolary and in person, between Matisse and two Dominican friars, Marie-Alain Couturier and Louis-Bertrand Rayssiguier, and Monique Bourgeois, who both nursed and modelled for Matisse in 1941-2 before herself joining the Dominican Order, where she took the name Jacques-Marie.

Couturier, in particular, came to the project both as an artist with an affinity for modernism himself and as the sometime editor of the journal L’Art Sacré. Founded in 1935, L’Art Sacré was, among other things, a revolt against what Miller calls the “sumptuous but saccharine” naturalism of the prevalent aesthetic in religious art – as characterised by the work of Adolphe-William Bouguereau, for example. The journal advocated a ressourcement, a spiritual and artistic renewal through a return to the sources of Christian art on either side of the Great Schism. It also sought to reconnect modernity to the sacred through a re-engagement with the thought of Thomas Aquinas. In this it followed the work of the contemporary Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain in his exploration of Thomist theology, not least with regard to concepts such as ‘wholeness’ and ‘integrity’, ‘harmony’ and ‘radiance’ in beauty and art.

The chapel echoes the structure of Jazz: luminous biomorphic shapes in the tall, elegant almost- claustral stained-glass windows juxtaposing white-tiled walls carrying monochrome images of the Madonna and child, of Saint Dominic and of the Passion. These are are unlike anything else in Matisse’s work: intensely simple, rawly hieratic, brutally direct. The effect, Miller writes, is of “presences more than depictions”, a phrase that consciously echoes Wassily Kandisky’s distinction between images that are merely representational and those that make a spiritual reality present.

But what is the nature of the spiritual reality, the immanence, that Matisse’s chapel makes manifest? In the early stages of the project, Matisse had written that he aimed “to lead colour through the paths of the Spirit”, and to be in the chapel, Miller writes, is to be “set within the architecture of the book, or rather the two books of nature and grace” – that is, creation and scripture – represented by colour on the one hand and line on the other. To move through the chapel, then, is to move through the articulation an argument, a spatial arrangement of ideas about grace and suffering, creation and redemption that are resolved by the divine gift of light, which is to say, love.

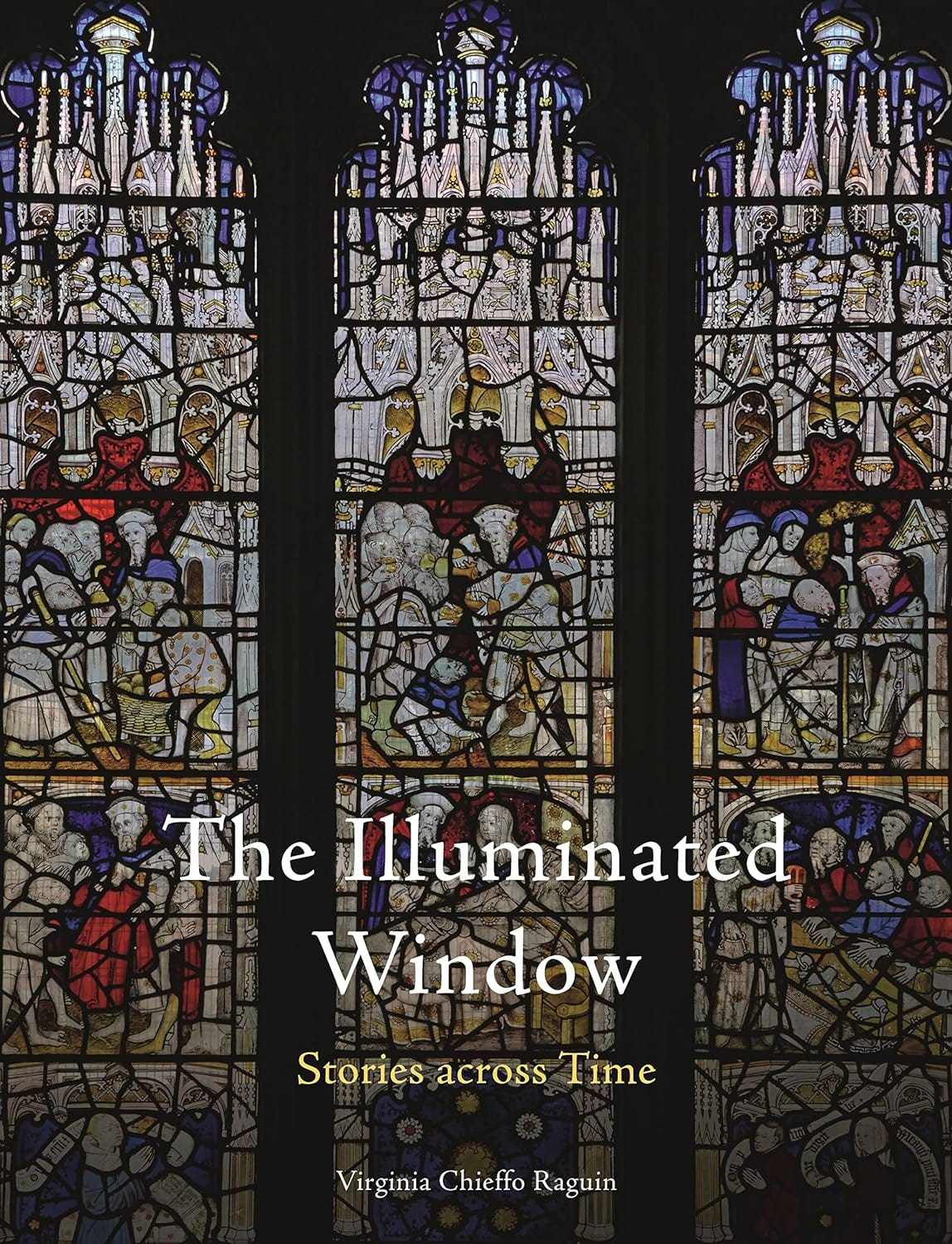

The narrative possibilities of stained glass alone are at the heart Virginia Chieffo Raguin’s new book The Illuminated Window: Stories Across Time, which explores developments in the art from the 12th century to the present day. Most chapters focus on the function of glass within specific buildings, from Gothic cathedrals and parish churches to the Tiffany Chapel; but the preponderance of the book is on religious uses of the art form in the medieval and Renaissance periods.

That subtitle is important: The Illuminated Window is in large part about the the capacity of stained glass to perform exegetical tasks – most obviously in the depiction of scriptural or hagiographic narratives – although Raguin also explores how modern abstract installations, such as those of Gerhard Richter at Cologne Cathedral, can “invest space with a timeless and immaterial present”.

Canterbury Cathedral’s cycle of twelve typological windows, for example, pairs events from the Old Testament with events from the New, showing how the former prefigure the latter. The prophet Balaam points to a star in a scene from the Book of Numbers; the scriptural text, in Latin, reads “A Star shall come out of Jacob; a Sceptre shall rise out of Israel”. In the next frame, the same star leads the three kings to the infant Christ.

At St Mary’s in the Cotswold town of Fairford, whose early 16th-century stained-glass is a remarkable and rare survival of succeeding waves of protestant iconoclasm, a sequence of windows illustrate the life of Christ. As Raquin notes, the choice and treatment of theme parallel contemporary meditative writings such as those of the monk Nicholas Love, whose The Mirror of the Blessed Life of Jesus Christ was immensely popular in England in the century prior to the Reformation. The window that depicts Christ’s Transfiguration, for example, emphasises comfort and consolation: it also shows the resurrected Christ returning to console his mother.

One might say that exegesis of God’s work is the conventional language of stained glass, even where a narrative is only referenced through a single image: just one scene from a series of designs for the Passion, Chieffo writes, “such as Christ being led to Jerusalem, allows the viewer to fully empathise with a saviour willingly accepting humiliation, pain and ultimately death for the sake of another”.

But the nature of the material – and the way it mediates light, the creation of which is God’s very first command in Genesis – means that at a deeper level, it also serves to realise the sacred, to make God’s breath visible. Illuminated windows are where the light of creation meets human art and craft, God and man working together in an infinitely shifting present: light moves and changes the way both art and light are received, modulating, elaborating and restating its music. Spiritual reality is always present then, to pick up on Kandinsky’s distinction, because the image can never simply be representational: it is necessarily always infused by light, which is sacred.

What then happens to the medium when it moves out of sacred spaces into secular or domestic domains? In ecclesiastical settings, from Canterbury to Vence, the creation of particular stained glass windows has always been in some sense a conversation between the artist or craftsman and the patron – the latter often being a community, be it a convent, a trade guild or congregation. In these news settings, Raquin shows the glass articulating a different kind of story. In Renaissance Switzerland, “small panels [were given] as testimonials of solidarity and friendship”, or as tokens of intense civic pride, between individuals, guilds, towns and cantons. Meanwhile the development of painted glass roundels in Northern Europe, enabled artists to bring the nuances of print and engraving design to their work; the dialogue between the two practices gave patrons and clients more precise control over the images they commissioned.

While some of these new forms of work celebrated secular identities, many still drew on scripture, affirming intimate affinities between biblical narratives and those who commissioned or received the images. The village of Lotzwil near Burgdorf gave a window with a lavish representation of the Judgement of Solomon to one Johannes Trachsel, a goldsmith who performed judicial functions for the municipal council. A roundel at the Hospital of St Elizabeth in Lier features the meeting of Jacob and Joseph set in an otherwise decorative panel. These windows sat somewhere at the intersection of private, interior and public, exterior lives – but they remind us how much both worlds were illumined by the sacred.

Both books explore in very different ways the exegetical capacity of architecture, intersecting in the narrative possibilities of stained glass. Metaphors of illumination come all-too-readily to hand in responding to them. But if light itself co-exists as both a metaphor for the sacred and an expression of it, then stained glass is similarly ambiguous in the stories it tells – a thin and gorgeous veil between the figurative and the real, the material and the divine. To move through the space before it is to move beyond the human and to be in light. A spiritual resuscitation, howsoever brief.

This is an extended version of a review that first appeared on Englesberg Ideas last year.

Lovely to be reminded of the glorious Matisse chapel. I hadn’t heard of the book.

This is a very nice review of a pair of books I would probably never otherwise have encountered. Thank you.