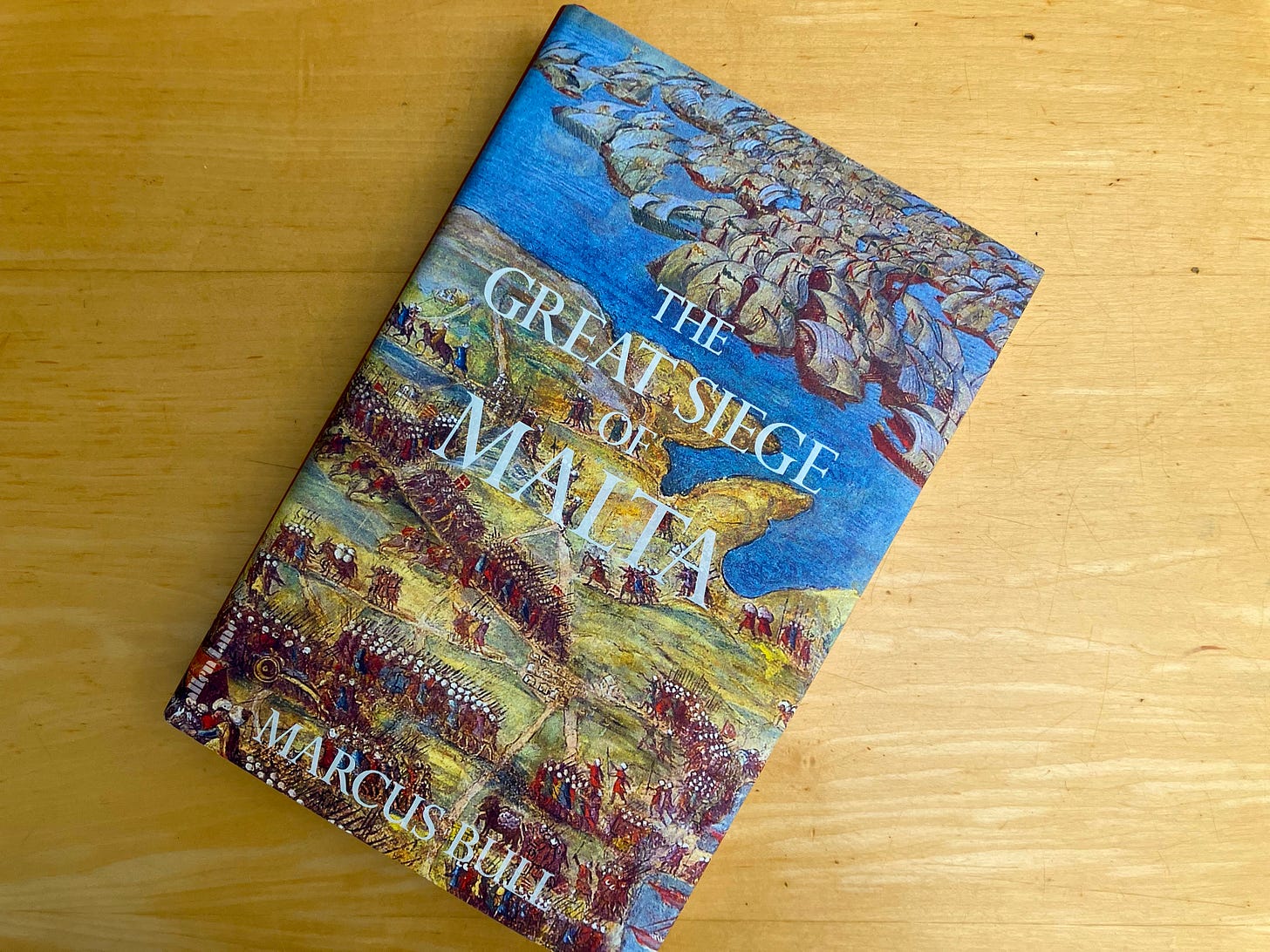

Review: The Great Siege of Malta by Marcus Bull

A nuanced account of a rare but epic Christian victory against the Ottoman Empire.

It remains an extraordinary story. On 18 May 1565, a vast Ottoman armada appeared off the shores of Malta. It comprised some 130 galleys, with at least sixty other vessels in tow. On board were perhaps 25,000 soldiers. Another five thousand or so corsairs would join forces with them later.

The Maltese archipelago was held by the Order of St John, which was founded in the Holy Land in the 11th century. Also known as the Hospitallers, they established hospitals wherever they went – on board ship, on a beach in the Bay of Naples – but were primarily a military order. They were also far from numerous: there were around 580 of them on Malta, of whom 470 were knights. They were supported by several thousand professional soldiers as well as the local population.

It was an unequal fight, but the knights and the islanders held on. A key fort, St Elmo, fell in June after three weeks of bombardment and slaughter. Other defences held. A relief force of some seven hundred men arrived in early July. A larger one, comprising 9,600, came in early September. By the time the invasion fleet finally departed on 12 September, one knight reckoned that the Ottomans had fired their cannons seventy thousand times.

The victory was quickly memorialised as Christianity’s counterpunch against the relentlessly expanding Ottoman Empire. A dramatic painting of it adorns a passage to the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican. It had ‘a significant impact on the collective psyche of a Christian Europe beleaguered by a long history of Ottoman military success’, writes Marcus Bull in his engrossing new study. But he is sceptical of heroic narratives; his subject is less the siege itself than the outsized claims made about its significance.

Malta itself was of little strategic significance at this period – that came later with the expansion of non-coastal east–west traffic in the Mediterranean – and, good harbours aside, had little to recommend itself. It only produced enough food to feed its population for a third of the year. When the Hospitallers surveyed the archipelago in 1524, prior to taking possession of it from Emperor Charles V six years later, they described it as ‘wretchedly subject to the rapacity and depredation of infidel corsairs’. In 1551 such corsairs, with support from the Ottomans, seized five thousand people from Gozo, the archipelago’s second island, and enslaved them. ‘This wretched island of Malta’, one Italian knight called it, looking back.

How, then, did the Hospitallers prevail? Bull is reluctant to place too much emphasis on structural reasons for the Ottomans’ defeat. Yes, they were at the outer limits of their operational range in the Mediterranean, but a similar-sized armada made short work of taking Tunis the following decade. There is little evidence that their logistics failed them.

Rather, Malta was held by the finest of margins because a number of small but cumulatively decisive factors swayed the contest in the Hospitallers’ favour. The Ottomans suffered disproportionately heavy losses among their elite troops in the capture of St Elmo. The Hospitallers had prepared carefully – or carefully enough, at least – for the siege and had sufficient supplies of gunpowder, food and water. And they were lucky to have the passionate support of the local population: one Christian source talks of the furor di popolo. Ultimately, Bull concludes, the defenders ‘just about held on because they were very, very lucky’.

For Bull, the 1565 siege of Malta was a ‘momentous, epic event that changed very little’: it had next to no impact on Ottoman ambitions or capabilities, either in the Mediterranean or elsewhere – although he does note that Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent was himself an indirect casualty of it. Stung by the defeat, Suleiman chose to lead a siege of Szigetvár in Hungary the following year personally. He died there in his tent.

Bull’s account of the siege itself is lucid and dispassionate. He has a sharp eye for bombast – representing the failed defence of St Elmo as a heroic act of self-sacrifice, for example – that might obscure uncomfortable truths. He is likewise resistant to any reading of it that implies a ‘clash of civilisations’, identifying the religious rhetoric on both sides as simply a means to ‘animate and exacerbate conflicts with roots in political and economic competition’. The siege is best understood, he argues, in the context of imperial competition in the Mediterranean, in which legitimate trade, the piracy-adjacent activities of corsairs and vulnerable pilgrim voyages all played their parts. This was ‘a convulsive moment in the chaotic history of an unstable, fragile zone’.

Bull also sees analogies in the Ottoman rivalry with the Portuguese in the Indian Ocean and tensions between Spain and France in the Americas. News of Spain’s destruction of the largely French Huguenot settlement at Fort Caroline in Florida the same year as the siege was greeted at the Spanish court with more joy ‘than if this had been a victory won over the Turk’, according to the French ambassador. ‘For they used to say, and still do, that Florida matters much, much more to them than Malta.’

Bull has set himself a challenging task: to convey the drama of the siege and the myths that grew out of it while downplaying, if not denying, suggestions of its wider historical importance. It’s a difficult balancing act, but one he pulls off with aplomb.

This review first appeared in the February 2025 issue of Literary Review.

Thanks for this. I’m descended from the locals that fought in the Great Siege and I spent some time in Malta last year studying up on the history of the island including the Siege. Yes the Knights definitely dined out on it for years and we continue to enjoy their legacy in terms of their patrimony of the island. I’ll have to have a read!