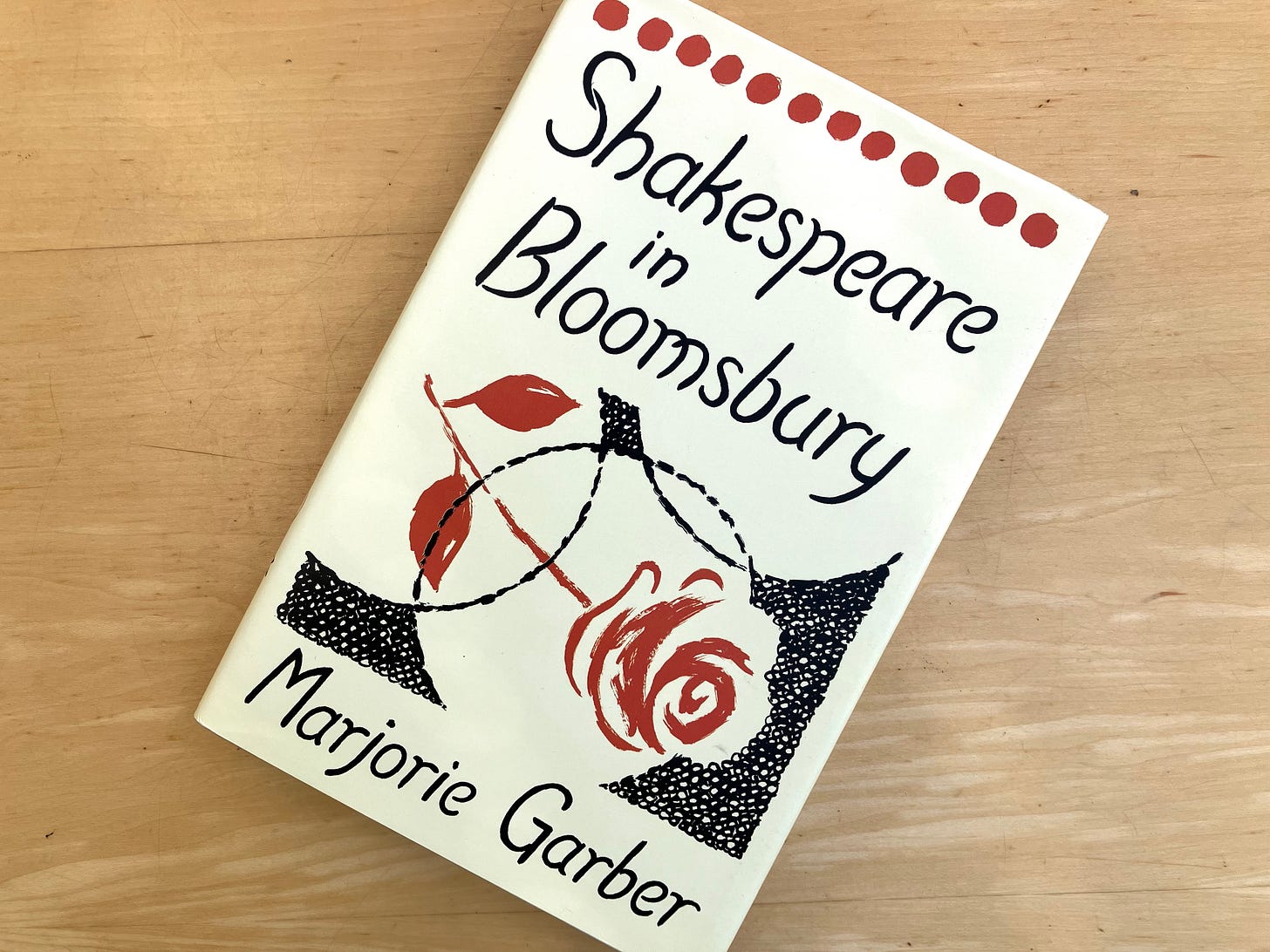

Review: Shakespeare in Bloomsbury by Marjorie Garber

An extended version of my review for The Spectator to mark the book's publication in paperback

In late November 1935, Virginia Woolf went to see a production of Romeo and Juliet. She was not overly impressed. “Acting it,” she wrote, “they spoil the poetry”. Harsh words, you might think, for a cast that included John Gielgud, Laurence Olivier and Peggy Ashcroft. But Shakespeare on the stage was always something of a bête noire for the Bloomsbury group.“We, of course, only read Shakespeare,” the art critic Clive Bell later said; the Shakespeare that really mattered was the one on the page.

Who was that ‘we’, though? Marjorie Garber’s understanding of the group’s membership is, relatively speaking, quite capacious. It encompasses Virginia Woolf and her siblings; numerous alumni of the Cambridge Conversazione Society, also known as the Apostles; and their children and friends. The question Garber poses in Shakespeare in Bloomsbury, however, would add one more to the list. To what extent, she asks, might we consider Shakespeare himself a member, ‘absent-present’, in Woolf’s phrase, in their thought and conversation?

Woolf’s introduction to Shakespeare came largely through another absent presence in her life, her older brother Thoby – himself an Apostle – who died in 1906. His loss haunted her; she considered dedicating Jacob’s Room to him in 1922. But his passion for Shakespeare left its mark: “He would sweep down upon me, with his assertion that everything was in Shakespeare,” she remembered, “he was ruthless; exasperating me; downing me, overwhelming me.”

There is a similarly engulfing physicality in Woolf’s reading of Shakespeare that roars off the page. “I was reading Othello last night, & was impressed by the volley & volume & tumble of his words,” she wrote. “I never yet knew how amazing his stretch & speed & word coining power is… things I could not in my wildest tumult and utmost press of mind imagine.”

Late in life she wrote of how “theatre must be replaced by the theatre of the brain… the audience by the reader”. It sounds a cold, passive formulation, but for Woolf it was anything but: the words on the page are more real, more intense than a mere actor could ever be. “I read Shakespeare… when my mind is agape & red & hot,” she wrote.

Garber’s account of Woolf’s engagement with Shakespeare, and the way she used it in her own work, is superbly detailed and forms the heart of the book. It offers a brilliant and sustained – even beautiful – exegesis, book by book, line by line. I say beautiful both because it illuminates the aesthetic premium Woolf placed on language, and because the quality of attention from both Garber and Woolf is itself of such intensity.

Woolf called him ‘Shre’ in her diaries, a casually intimate nickname reserved for her own thoughts. When she noted the thoughts of others, she typically reverted to ‘Shakespeare’, as if her particular intimacy with him must remain inviolate – a sense heightened by her outrage at the way Sir Walter Raleigh, first chair of English literature at Oxford, called him ‘Billy Shax’. “This shocks me,” she wrote to Vita Sackville-West.

No other member of Bloomsbury approached this kind of identification with Shakespeare. Some – Lytton Strachey and Desmond MacCarthy, for instance – wrote about him. For George ‘Dadie’ Rylands, meanwhile, Shakespeare was a career: a Cambridge don, he also directed countless productions of Shakespeare and taught, among others, Ian McKellen and Derek Jacobi, Peter Hall and Trevor Nunn. Ironically, perhaps, for a member of the Bloomsbury set, Rylands’ influence on the performance of Shakespeare, and in particular on the speaking of the language, has been significant. John Maynard Keynes, meanwhile, helped established the Cambridge Arts Theatre in 1936 and shaped the founding of the Arts Council in 1945.

But the overriding sense is one of Shakespeare as an everyday cultural companion. Sending his wife, Russian ballerina Lydia Lopokova, some plays, Keynes wrote: “I send you… four little Shakespeares… which you can take into the bathroom or carry in your bag or on the bus”. In this there is an echo of Leslie Stephens, Woolf’s father, who wrote in 1887 that “we are quite at ease with that essence of Shakespeare which is compressed into a book. We can put him in our pockets… and treat him as familiarly as a college chum.”

But to what extent was this deep familiarity with Shakespeare simply part of the baggage of an English literary education in the period? Baggage here is a metaphor, but it is literally true too. Vita Sackville-West took the complete works with her when her husband, Harold Nicolson, received a diplomatic posting to Persia. Leonard Woolf did the same when posted to Ceylon; Duncan Grant likewise when he moved to Paris.

Garber herself notes in passing the 19th-century economist William Stanley Jevons referencing Sonnet 66 in his private journal, for example. How meaningful is it, then, that John Maynard Keynes once played the part of Dogberry in Much Ado About Nothing at school, or that Quentin Bell echoed Twelfth Night in comparing MacCarthy’s daughter to patience on a monument? The reader recognises the authorial need to be exhaustive, but one’s interest sags a little beneath it. As Vanessa Bell wrote of an argument about King Lear with Lytton Strachey, “it sounds very dull written down”.

Woolf was no admirer of academia: to be an English student was “to sip English literature through a straw” she wrote, which provoked the critic QD Leavis to damn in turn the Bloomsbury set’s “boudoir scholarship… and belletrism”. But as Gerber notes in an elegiac coda to the book, “A century of academic scholarship and technological revolution has changed, inevitably and probably irrevocably, how Shakespeare is read.” People – even the privileged sort of whom Bloomsbury were a part – no longer read Shakespeare to one another by way of an evening’s entertainment. The kind of community of readers they represented is no longer possible.

Few of us reread Shakespeare simply for pleasure. How many outside education read him at all? Contemporary concerns – race, feminism, gender – dominate studies. TS Eliot’s point, made about Strachey and others, that “if we can never be right [about Shakespeare], it is better that we should from time to time change our way of being wrong” still applies here.

MacCarthy wrote that typical responses to Shakespeare were akin to peering at “some dark, rich, glazed” portrait of the playwright hung “in a bad light” which reflects “the features of those who peer curiously into it”. Woolf noticed the same effect in Hamlet: “the critic sees something moving and vanishing… as in a glass one sees the reflection of oneself”. As if to prove the point, Garber quotes Freud on Shakespeare the ‘great psychologist’. What then do our concerns say about how we see ourselves these days?

Strachey, in the introduction to Rylands’ Words and Poetry published by the Woolf’s Hogarth Press – oh, how cliquey it all was! – quoted Mallarmé: “poetry is not written with ideas; it is written with words”. Shakespeare in Bloomsbury reflects that. It is a powerful embodiment of the process it describes: the deep rewards of rapt attention to great writing. But Garber is right: we are a long way adrift now from Woolf’s aesthetics of language – far from the pebbled shore, the pearls and old bones – and further out to sea all the time.

This is an extended version of a review that first appeared in The Spectator in January 2024.

I think you might like the long section on Woolf and Shakespeare in this book, in that case!

I've always liked John Keats' idea of synchronised reading of Shakespeare to keep people who are far apart a sense of togetherness.

In December 1818, he wrote from London to his brother George and sister-in-law Georgiana in Kentucky with the following suggestion: "I shall read a passage of Shakespeare every Sunday at ten oClock – you read one at the same time and we shall be as near each other as blind bodies can be in the same room."

Not sure they did it and of course time differences wouldn't have helped. After all 10 o'clock wasn't even 10 o'clock all over Britain at the time. However in Keats sense of togetherness the Keats-Shelley house during Lockdown did have a 'synchronised' reading group at noon on Wednesdays - what 'noon' you chose was left to the individual readers.