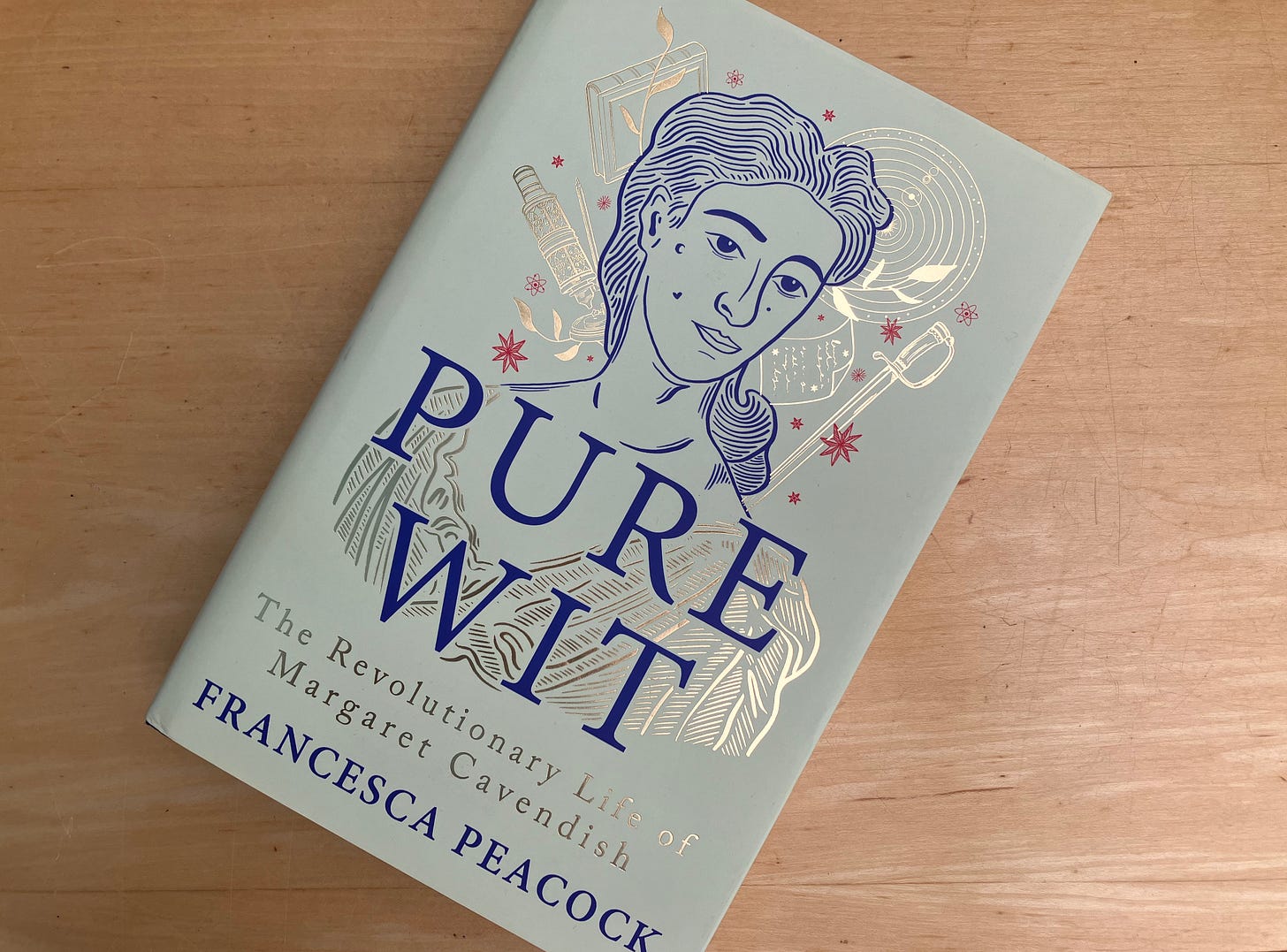

Review: Pure Wit: The Revolutionary Life of Margaret Cavendish by Francesca Peacock

An extended version of my original review for Engelsberg Ideas to mark the publication of Pure Wit in paperback this week

“All I desire is fame,” wrote Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, in the preface to her first book, a collection of poetry, in 1653. “Fame is nothing but a great noise… therefore I wish my book may set a-work every tongue.” As a statement of the workings of celebrity it is remarkably modern. But it was also a statement of intent. Cavendish always knew how to make an entrance, even on the page.

In Restoration London, she was notorious. She arrived at the premiere of her husband’s play The Humorous Lovers – according to one man’s over-heated account – in a carriage pulled by eight white bulls; the neckline of her bodice plunged so deeply it left “her breasts all laid out to view” and displayed her “scarlet trimmed nipples”, he wrote. She designed her own clothes, which is to say she set her own fashions, as she did in all things. When Sir Peter Lely painted her portrait, she is standing authoritatively in her red ducal robes, but wearing a man’s black velvet feathered hat. Her plays – written to be read, not performed – are full of puissant women, fighting wars, despairing of their marriages, living in happy man-free utopias. Despite being painfully shy in person – in one play she dramatises herself as Lady Bashful –she picked fights in print with the likes of Thomas Hobbes and Robert Hooke.

If some of this sounds frivolous, for Cavendish the fight for attention, for a space to think and a space to be heard, was anything but. She dazzled contemporaries in ways that sometimes puzzled and bemused them; “the whole story of this lady is a romance,” Pepys wrote. But they took her seriously too. The newly-formed Royal Society opened its doors to her, the first time they had done so for a woman; they would not elect a female fellow for close to three hundred years. After her death in 1673, her reputation faded. One Victorian worthy dubbed her Mad Madge; Virginia Woolf wrote that her work was “congealed in quartos and folios that nobody ever reads”. If that was true a century ago, it is not so now. She is back in print; some of her dramas have been staged; scholars of philosophy such as Deborah Boyle and David Cunning analyse her thought. Why should that be the case? Francesca Peacock in Pure Wit: The Revolutionary Life of Margaret Cavendish, her debut work, is here to tell us.

In some ways we misrepresent her by referring to her merely as Margaret Cavendish. Peacock is keen to highlight that Cavendish wasn’t born into the aristocracy, but she was from a wealthy and prominent family of Essex gentry nonetheless; not everyone had the status to host Maria de Medici, mother of Henrietta Maria, Charles II’s queen, as Margaret’s family did in 1638. Margaret’s father, Thomas Lucas, had died in 1625 when she was two, and her mother ran both the family estates and its business interests. The family – and certainly its women – were close. Even after they married, Cavendish remembered, her older sisters “had no familiar conversation or intimate acquaintance with the families to which each other were linked to by marriage” but went about “in a flock together”. Perhaps her utopias, like her politics, were nostalgic too. Margaret received little intellectual education; she was something of an autodidact. Perhaps relatedly, she regarded the mind as the one place a woman could be free, reigning sovereign without reference to men or their social strictures. “My mind is become an absolute monarch, ruling alone” she wrote. Her wit was pure because it was strong, but also because it was unconstrained.

The civil war broke the family, as it did the nation. In August 1642, the family home was ransacked by a local mob sympathetic to Parliament. Livestock was slaughtered or stolen, the house looted, the family vault broken into, its coffins desecrated. Margaret’s mother was paraded through the streets; someone attacked her with a sword. It seems likely Margaret was present, although the evidence is inconclusive. The following year, she fled one women-centred world for another, leaving Colchester for the royal court, then based in Oxford, and a role as maid of honour in the private chambers of Henrietta Maria. When the queen went into exile in France in 1644, Margaret went too. While in exile, the family house would be raided again: soldiers broke into the tombs of her mother and one of her sisters, both recently dead, cut the hair from the corpses and make merry with the wigs they made. Two of her brothers, both royalist soldiers, would die in the war, one of them executed by a Parliamentary firing squad in 1648.

In 1645 she married William Cavendish, then marquess of Newcastle, leader of the defeated Royalist forces at Marston Moor, some thirty years her senior and a widower too. He was, Henrietta Maria thought, a “fantastic and inconstant” man; the marriage would have its problems but in many respects they were well matched. Charles II would make William a duke after the Restoration, and there is no escaping the importance of title and social privilege to Cavendish. One of her late title pages hails her as “Thrice Noble, Illustrious, and Excellent PRINCESS, the Duchess of Newcastle”. Princess was a leap, even for a duchess. But arguably even that wasn’t enough. “My ambition is not only to be Empress, but Authoress of a whole world,” she wrote in The Blazing World, her remarkable 1666 fiction which, as Peacock writes, is “part scientific treatise, part utopian philosophy, and part proto-science fiction [and] wholly radical”. Social status was key to her identity; it was also key to her philosophical and creative vision.

Cavendish was a devout royalist who believed the pre-war social order was the right and natural state of things. “Dissent from this could not, for her, be a product of rational political thought,” Peacock writes. “She did not so much disagree with the anti-Royalist side, as utterly fail to understand them.” Arguably, she thought their arguments irrelevant; she saw such disputatiousness not as a product of reason so much as a symptom of disorder, of malignant spirits. Even in her groundbreaking discussion of atomism, as Peacock notes, it is “factious atoms” that make “all go wrong”.

In fact, Cavendish’s devotion to monarchy far outpaced any religious feeling she may have had. “It is better, to be an Atheist, than a superstitious man,” she wrote, “for in Atheism there is humanity, and civility, towards man to man; but superstition regards no humanity.” Her yearning for fame, she said, sprung from “doubt of an after being”. One vicious epitaph damned her as “the great atheistical philosophraster”. She probably wasn’t an atheist, as we would understand it. But she was far from conventional in her theology, all the same. This is, of course, a theme with Cavendish. Her capacity to confound expectation persists: the subtitle of Peacock’s book proclaims hers a revolutionary life, and Peacock rightly wants to claim her as a radical thinker and a proto-feminist. But that emphasis seems to us to sit awkwardly with Cavendish’s firm belief in privilege and autocratic power, and with the centrality of order, balance and authority to her thinking. “History withers if we only consider the parts of it that feel relevant to our own predicaments,” Peacock writes; yet we are still challenged by Cavendish’s very seventeenth-century mix of emancipatory and conservative thought.

It is her complexity, as much as her trailblazing originality, that makes Cavendish such a fascinating subject for biography. It is easy to sympathise with Cavendish’s predicament when her husband asks her to pawn a dress to pay for food; it is less easy when she avoids this necessity by making her maid pawn her own possessions instead. Whatever the opposite of intersectional feminism is, Cavendish surely defines it. Unable to have children herself, she wrote with vigorous disgust for pregnant women, including one “rasping wind out of her stomach, as childing women usually do, making sickly faces to express a sickly stomach”.

Nevertheless, Pure Wit is in part also a book about women’s agency in mid-seventeenth-century England, from the women organising the defence of their defending their homes – well, castles – against approaching armies, to cross-dressing soldiers, poets, pamphleteers and a printer. On this reading, Cavendish was both sui generis and part of a wider historical moment in which women were far more active and vocal than traditional histories have tended to recognise. Moreover, Peacock places her in a contemporary literary and intellectual context, citing largely neglected late-seventeenth-century campaigners for women’s rights such as Bathsua Makin, Mary More and Mary Astell. Cavendish “was the epicentre of a new wave of women’s writing, education, and thinking,” Peacock claims. While texts such as The Convent of Pleasure posited women-only spaces dedicated to serious pleasures of the mind and, sometimes, of the body, others, such as the Philosophical Letters, were framed by what Peacock calls “a constructed community of female readers and writers”.

The nuanced way that Peacock argues for Cavendish’s place in feminist history is one of the book’s great strengths. Peacock sees analogies, for example, between Cavendish’s work and twentieth-century writing by Leonora Carrington, bell hooks and Shulamith Firestone. That is not to say that she sees influence, however. Rather she sees deep continuities in women’s experience in a pervasively and oppressively male-dominated society. She notes too that the Cavendishes almost certainly owned a sumptuous illuminated manuscript of the works of the early fifteenth-century writer Christine de Pizan, commissioned by Isabel of France around 1413 and now in the British Library. “De Pizan is clearly an influence on Cavendish’s work,” Peacock writes, noting the parallels between the former’s Book of the City of Ladies and The Blazing World, among other works. Those continuities of separatism, hope and experience stretch both ways.

What Cavendish would make of the 21st-century resurgence in her fame is anyone’s guess, but it is hard to think she would be displeased. Pure Wit may not quite do her justice – what could? – but it reminds you why she should be remembered, read and celebrated in the first place. Cavendish’s thought can be dauntingly obscure, and at times this reader struggled to follow Peacock’s account of it. Nevertheless, this an alert, thoughtful, clear-sighted exploration of an extraordinary life and a remarkable mind, written with lucidity and verve. “Though I cannot be Henry the Fifth, or Charles the Second,” Cavendish once wrote, “yet I endeavour to be Margaret the First.” That she certainly was.

Love "Mad Madge." Remember reading Katie Whitaker's biography (same title) aeons ago...Seem to recall she was v. strong on the effect of exile in Holland on M.C.'s work.