Bad choices and dangerous friends: the fugitive promise of George Gascoigne

Why one of Elizabethan England's great literary innovators died a broken man

Sometime in London in the autumn of 1577, Gabriel Harvey, the son of a Saffron Waldon ropemaker and a self-consciously brilliant young Cambridge academic, opened up his copy of The Steele Glas, a long satirical poem, and turned to one of the volume’s three commendatory verses. It was signed: “Walter Rawely of the Middle Temple”. A compulsive – indeed, obsessive – annotator of other men’s work, Harvey paused to note down a rebus he had heard, perhaps among his friends in the circle around the Earl of Leicester, based on the poet’s name:

The enemy to the stomach, and the word of disgrace

Is the gentleman’s name, that bears the good face.

Beside this, in the margin, Harvey wrote by way of explanation: “Rawley”. This, a poem for his friend Gascoigne, was Ralegh’s first step on the public stage.

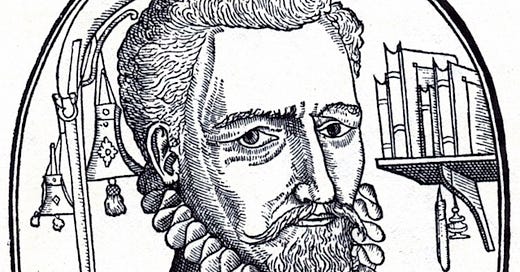

But when Gabriel Harvey picked up his copy of that book, the first thing he would have seen was a portrait of the author on the verso. George Gascoigne looks out at the reader, books over his left shoulder, an arquebus and other weapons over his right. Beneath the portrait is Gascoigne’s latest motto, tam marti quam mercurio – made for war as much as wisdom. This, like the commendatory poems, is another kind of advertisement, a personal strap line, articulating what ‘brand Gascoigne’ had to offer. Writing retrospectively, to defend his first foray into print in 1573, Gascoigne would say:

Being busied in martial affairs (whereby I also sought some advancement) I thought good to notify unto the world before my return, that I could as well persuade with pen, as pierce with lance or weapon: So that yet some noble mind might be encouraged both to exercise me in time of peace and to employ me in time of service in war.

But the motto had another significance, too, exemplifying Gascoigne’s personal influence on Ralegh. After Gascoigne’s death – he died on 7 October 1577, at the Lincolnshire home of another soldier-turned-writer George Whetstone, around the time Harvey bought The Steele Glas – Ralegh would appropriate the motto for his own. A man of action and a man of judgement: that was the pitch, and like today’s corporate slogans, it was notionally accurate, but also wishful. The description approximated reality, but it was primarily positional. It said much more about how Ralegh and Gascoigne wanted to be seen, than how they actually were.

The scabrous pampleteer Thomas Nashe later offered another take on the motto, which might reflect on either man: the phrase, he said, excused poets their “dagger drunkenness [which makes] every stanzo they pen after dinner… full-pointed with a stab”. Elsewhere Nashe associates it with “the nature of an upstart”, “a malcontent… a squire of low degree… who complains like a decayed earl, of the ruin of ancient houses”. He could be referring to many of the gentlemen who sought their fortunes at the margins of the court; more than likely it is Ralegh he has in mind.

But to return to the portrait for a moment, it is not the motto, or the ephemeral signifiers behind Gascoigne that draw the eye. It is the face: worn, haunted, desperate, old and – as it turned out – a year from death. It is the face of a man cornered, an implication that is enhanced by the books and weapons: they frame him; but they also confine him. He is trapped between them – and the narrow choices they offer – and his eyes seem to say that he knows it.

Gascoigne’s reputation today, such as it is, is as a literary innovator: to him, the first English prose comedy; one of the first English tragedies; the first non-dramatic satire, which is also the first blank verse poem; one of the first English novels; one of the first English masques; the first piece of English literary criticism; and so on. His output was prodigiously diverse: lyric poetry, satire, moral tracts, drama, entertainments, war reportage – most of which, despite having been written over the preceding decade, flooded into print in the four years following 1573. It was an impressive achievement, recognised by contemporaries and successors even as they surpassed him.

Spenser, writing two years after Gascoigne’s death, recalled him as “a witty gentleman, and the very chief of our late rhymers… the gifts of wit and natural promptness appear in him abundantly”; Nashe, to whom praise did not come easily, said that he “first beat the path to that perfection which our best poets have aspired to since his departure”; Shakespeare paid him the compliment of stealing one of his plots. Ralegh liked The Steele Glas enough to quote one of its witticisms, albeit without acknowledgement, in a letter to the Earl of Leicester in 1581. Leicester himself commissioned Gascoigne to write the entertainments for Elizabeth’s summer visit to his palace at Kenilworth in 1575.

All those firsts are significant, not least because there were no seconds: Gascoigne rarely followed anything up or repeated himself, thus failing to build a consistent reputation for anything – except, perhaps, inconstancy, which was not a particularly saleable commodity. The superficiality of the man, but also something of his charm, is apparent in his swaggering admission that he wrote, as much as anything, for the pleasure of celebrity: “A fancy fed me once, to write in verse and rhyme…/To hear it said there goeth the man that writes so well.”

Born around 1535, George Gascoigne was the elder son of a prosperous and successful Bedford landowner. Despite such a beginning, Gascoigne’s life was dogged with failure and debt, in part occasioned by his attempt to marry into money by wedding Elizabeth Breton, a wealthy widow. The catch was that she had already remarried – with one Edward Boyes. The ensuing dispute dragged through the courts for years – Gascoigne was an enthusiastic if unsuccessful litigator – but also spilled out into the streets.

The diarist Henry Machyn noted with some glee on 30 September 1562 that there was “a great [af]fray in Red Cross Street between two gentlemen and their men, for they did marry one woman, and divers were hurt; these were their names, Master Boyes and Master Gascoigne gentlemen”. For reasons that remain obscure, Gascoigne also seems to have been disinherited by his father – a brutal blow, from which Gascoigne’s finances never really recovered. But familial relations were clearly complex: Gascoigne contested both his father’s and his mother’s will – from which he was also excluded – and on one occasion, at least, took a dispute over property with his brother all the way to court.

By the late 1560s he was studying law at Gray’s Inn, a choice which seems to have brought no discernable uptick in the success of his litigation. He would not, in any case, be called to the Bar, attempting instead to use the inns as a springboard to favour at court.

In haste post haste, when first my wand’ring mind,

Beheld the glist’ring court with gazing eye…

The stately pomp of princes and their peers,

Did seem to swim in floods of beaten gold,

The wanton world of young delightful years,

Was not unlike a heaven for to behold.

The seductions were obvious. The pitfalls, apparently, were not. Gascoigne spent prodigiously to pretend a status, a lifestyle, an attitude, he could not in fact sustain. By his own account, this was not only unsuccessful as a strategy, but also brought him close to ruin. “(All too late) [I] found that light expense,/Had quite quenched out the court’s devotion.” It was a scab Gascoigne returned to pick more than once in his work; elsewhere, he notes ruefully: “I left the court at large,/ For why? The gains doth seldom quit the charge.”

In any event, Gascoigne’s humiliation when it came was public. “He is indebted to a great number of persons for the which cause he hath absented himself from the city and hath lurked at villages near unto the same city by a long time,” wrote an anonymous enemy to the Privy Council around this time. Fifteen years later Nashe could still joke about “having sung George Gascoigne’s Counter-tenor” as a euphemism for debt, the Counter being one of Tudor London’s debtors prisons.

Gascoigne was not the first to seek both refuge from his creditors and possible personal fortune on the battlefield, “As though long limbs led by a lusty hart,/Might yet suffice to make him rich again”. Nor would he be the last to discover the near impossibility of such hopes. Gascoigne’s first campaign seems to have been Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s ill-fated Flanders expedition in the summer and autumn of 1572. Friendship with Gilbert seems to have been the sum of Gascoigne’s rewards, although there were also compensations in the form of material for future writings.

But Gascoigne’s military history, brief as it is, suggests that Tam marti quam mercurio was, in some respects, something close to a lie, that the very pose of the poet-soldier already represented a kind of failure, being in his case very much a last resort.

The same informer who railed against Gascoigne to the government had other complaints against him too: manslaughter; the writing of slanderous verse; a spy; “an atheist and a godless person”. The first of these is unsubstantiated as far we know, but hardly implausible; the second is undoubtedly true, since Gascoigne’s grovelling apologies for offences that are sadly now opaque to us are still extant. “Sundry well-disposed minds have taken offence at certain wanton words and sentences,” he wrote of his 1573 collection of verses A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, “and that also therewith some busy conjectures have presumed to think that the same work was indeed written to the scandalising of some worthy personages.”

The book affected to be a secretly published anthology of a number of gentlemen’s verses; in the close-knit world of London it could hardly have been better designed to excite gossip. Indeed, it is hard to take Gascoigne’s many repentences at face value: self-reformation and regret for the lovingly catalogued follies of youth may be key Gascoigne tropes, but he is evidently more than half in love with his life of error.

In any event, although those specific charges of offence are obscure, we can nevertheless see Gascoigne’s gift for indelicacy on full view in a 1577 poem for Elizabeth, seeking to capitalise on his perceived post-Kenilworth favour, in which, in a strikingly inappropriate passage, he imagines how the queen lays “her mighty mace aside/And strokes my head”.

It is, perhaps, atheism, the last of the complaints, that catches the eye most. But we might pause here to consider what atheism meant. It is not of course to be read literally: true atheism as we know it today was rare in Tudor England. Instead the charge – almost a curse given the grave legal perils that it tugged in its wake – paradoxically asserted both hidden loyalty to Catholicism, and therefore an implicit hostility to the reformed faith of the state, and being of no fixed religion, indifferent to credal and political faultlines except insofar as they offered personal advantage.

The latter was, if anything, viewed with perhaps even more distrust and disgust by the Protestant establishment than recusancy; indeed, horror of such politique sophistry was shared across the religious divide. It spoke to the uncertainty and fear that flourished in a riven society, the primal horror of the house divided against itself, an enforced proximity in which families, communities and nations alike felt themselves so interpenetrated that it was impossible to know who might play unwilling host to betrayal.

The charge of espionage is in a sense related, since it implies doubleness, duplicity, a willingness to serve more than one master with neither assured of your loyalty. Gascoigne, like many in his position, was certainly active in several intelligence networks, albeit at a fairly low level. But we have to caveat that knowledge immediately by saying that our awareness of his work comes in the last months of his life, postdating the Privy Council accusation by several years. On 15 September 1576, for example, he reported to Burghley on reaction at the French court to developments in the Low Countries. (A postscript on the fate of that summer wine harvest – “Wine must be excessive dear this year, their vineyards are destroyed with frost and hail” – might hint at Gascoigne’s lack of focus and general unfitness for such work.) Two months later he was carrying letters out of Flanders for Walsingham.

But it is also true that Gascoigne kept interesting company. On 19 March 1573 Gascoigne took ship for the Netherlands with “my chief companions whom I held most dear”: Ralegh’s first cousin Edward Denny; a soldier named Rowland Yorke; and a sometime pirate and spy named William Herle. Perhaps appropriately for Gascoigne, the ship nearly foundered and twenty men died; autobiographical as much of his work was, he mined the experience for a long poem.

Denny, twenty-five in 1572, would be a regular tilter at the Accession Day tilts through the 1580s, the decade in which he made his reputation in Ireland. But in the early to mid-1570s he was, like everyone it seems, scraping around for preferment, trying out both soldiering and privateering without making his mark at either, unless one counts the debatable honour of having his piracy drawn to the attention of Walsingham.

Yorke was a professional soldier, and like Gascoigne a veteran of Gilbert’s campaign the previous year, but his reputation was more complex, being “most negligent and lazy, but desperately hardy”, according to the great contemporary historian William Camden – loose, dissolute, audacious. He was notorious around London for having introduced to England foining – that is, thrusting or lunging – when duelling with rapiers,the additional dangers of which must be quite apparent. It was under Yorke’s tutelage that the Earl of Oxford killed one of his servants with his rapier.

The air of glamour that hung over Yorke would darken into infamy in the following decade after he, again in service in the Low Countries, sold the Flemish town of Deventer to the Spanish in January 1587. Like many professional men of war, Yorke regarded his primary duty as being to look after his men, something that the pusillanimous Dutch government in his view made impossible. He had complained before, writing to them from Zutphen that “hitherto you have been greatly wanting; firstly as to the two months of victuals, of which we have received none at all, and secondly as to… some means to clothe the poor miserable subjects of her majesty who are in your service, and now are dying of cold; yea more than two hundred since my coming.”

Yorke had been accused of treasonable dealing with the Spanish before, too, having been sentenced to death by the Dutch in 1584 for allegedly plotting to betray Ghent. Roger Williams, one of the most senior English soldiers, had to plead with Elizabeth’s government to intervene:

Rowland Yorke is like to be executed, unless there be some means for him from England, but it is no man lives without faults… Your honour must consider some are not saints. Yorke was a man which had carried credit a long time as well with the Prince of Orange and the States General as with them of Ghent, and for anything that I could perceive, was always at their devotion until they failed him both countenance and means to live… I will stand to it never Englishman in these wars did them greater service than Yorke… if her Majesty knew the value of the man, I think she would make some means for him. Had he been a Spaniard, an Italian, French, a Walloon or Burgonian, he had wanted neither credit nor means.

It did not help Yorke’s reputation with his allies that he was a Catholic. The Dutch wondered darkly after Yorke’s reprieve why “he, a stranger, convicted of treason, having served against them . . . [and] frequenting the mass with his beads, should not only escape but be in credit.”

Gascoigne’s own religion affiliation was less apparent, but although he seems to have been Protestant there is also evidence to suggest he too was content to equivocate on his loyalty if there was sufficient advantage at stake. Gascoigne was elected to sit as a burgess for Midhurst in Sussex in the 1572 parliament under the auspices of the Catholic Anthony Browne, Lord Montague, for whom he also wrote a wedding masque. And in an echo of Yorke’s travails, Gascoigne was widely suspected by the Dutch of having sold the town of Leiden to the Spanish in return for safe passage for his men in February 1574. He survived to escape Yorke’s fate, however: the Spanish, no doubt with an eye on his record for disloyalty, poisoned Yorke in February 1588.

As for Herle, like Gascoigne he was habitually debt-ridden. He was a regular purveyor of intelligence to Cecil, particularly from the Netherlands and Germany, to which he frequently travelled to avoid his creditors, and was also an occasional pirate for similar reasons. Towards the end of 1571, he had informed Burghley of an alleged plot to assassinate him, dreamed up by two young men named Edmund Mather and Kenelm Berney, who were planning either to stab Burghley as he walked in his garden or shoot him through his study window.

Mather, in particular, had obsessed about killing Burghley for years, and in a violent age stood out as something of a psychopath: “Mather often talked on whether it were better to execute an enterprise by a dag or dagger,” another witness observed. “He commonly threatened his enemies with stabbing, and exercised himself with a dagger, to prove how he might hold it the surest.” Nevertheless there is an implication that it was Herle who nursed such incoherent hatreds into the semblence of a conspiracy before revealing its existence to Burleigh. Mather and Berney were both executed in February 1572. Herle remained a loyal friend and advocate for Yorke, despite the latter’s betrayals.

References to Gascoigne’s links to Ralegh are usually limited to his prior friendship with Gilbert and Ralegh’s commendatory poem for The Steele Glas, but in reality they are more complex and thoroughgoing than that would imply. There is the network of associations through the malcontents of the Middle Temple, and the Inns generally, the likes of Whetstone, who found in sardonic moral superiority a substitute for the social status they believed to be their right. There is Edward Denny, Ralegh’s cousin and Gascoigne’s friend. And there is Thomas Churchyard, another soldier-poet from the generation before Gascoigne, who contributed commendatory verses to Gascoigne’s 1573 A Hundreth Sundrie Flowers. Both Churchyard and Gascoigne, together with the Earl of Oxford, another Ralegh contact, contributed verses to Bedingfield’s Cardanus Comfort of the same year.

Gascoigne’s commendatory letter to The Steele Glas, addressed to Lord Grey of Wilton, was written “amongst my books here at my poor house in Walthamstow, where I pray daily for speedy advancement”. The wooded village of Walthamstow, in the purlieu of what is now Epping Forest, was on the river Lea; the city was some six miles away to the south-west, visible beyond the flat expanse of marshland and the fashionable Hackney townhouses. Gascoigne seems to have lived on the eastern side of the parish, in the shadow of the forest. In better times, he had lived in a “capital mansion house” on Red Cross Street, which ran north from St Giles Cripplegate to Barbican, inherited from his wife’s first husband. Herle was living in Red Cross Street in the 1570s, and may have lived there at the same time as Gascoigne; Sir Humphrey Gilbert certainly had a house there a few years later. Gascoigne’s kinsman Martin Frobisher lived in the same parish; Frobisher and Yorke were first cousins. It was an insular, intense and perhaps claustrophobic environment.

Walthamstow was, no doubt, one of the villages “neere unto the… city” in which Gascoigne’s anonymous accuser reported him to lurk; it was not the address of a man who expected imminent preferment at court. Indeed, that rush into print in the early 1570s was no doubt less driven by a desire to “serve as a mirror for unbridled youth”, than by a desperate need for money. It is sometimes said that Gascoigne’s career was on the rise when he died, and he had, at least, won work from Leicester, Cecil and Walsingham in the years preceding his death. But these were not clients offering significant work or patronage. Several of his late letters speak bluntly of illness and poverty in terms that seem pitiful, even now: “without some speedy provision of good provender I shall never be able to endure a longe journey, and therefore am enforced to neigh and bray unto your good Lordship” he wrote to Nicholas Bacon in January 1577, underlining the point – while also wrily sweetening any distaste at the brazenness of his plea – with an artful sketch of himself as an old nag.

It is tempting, considering Gascoigne’s relationship with Ralegh, to focus on those aspects of greatness that Gascoigne undoubtedly had and which he shared with Ralegh – originality, intellect, courage – to the neglect of his flaws. But the truth is that the Gascoigne Ralegh knew, for all his connections and for whatever glamour we may think accrues to his military adventures and literary achievements, was a failure – at best, a serial under-achiever. Harvey’s ultimate assessment of his sometime friend Gascoigne is damning – but judicious:

Want of resolution and constancy, marred his wit and undid himself… Many other have maintained themselves gallantly upon the sum of his qualities… It is not marvel, though he had cold success in his actions, that in his studies and loves, thought upon the wars; in the wars, mused upon his studies and loves.

This is a greatly extended version of material about Gascoigne in my book The Favourite, about the young Walter Ralegh and his relationship with Elizabeth I.

Wonderful article! You capture the spirit of the moment so beautifully. There seems to be something of a Gascoigne revival, and rightly so!

Fascinating and head-spinning. People will always hate a person who raises the very doubts they share but are afraid to reveal. One interesting bit, from my view, is that I know a man named George Whetstone, a violist. Not sure why I am mentioning this, but it leaped out at me, and I wondered if names always indicate lineage and association.