Hosannas and hatchet jobs

The how and why of the reviews I write: pitching for commissions, the process of reading and writing, and the rules I try to stick to along the way

I am a great fan of Stephen Potter’s quartet of Lifemanship books – Gamesmanship, Lifemanship, One-Upmanship, and Supermanship – published between 1947 and 1958, which are probably best known today through the 1960 Terry-Thomas film School for Scoundrels. The books are at once a parody of self-help books and a glorious satire on British middle-class mores in the middle of the twentieth century.

They are also delightfully perceptive of behaviour. There’s a reason words like gamesmanship - defined by Potter as “the art of winning without actually cheating” – entered the language: they describe with waspish accuracy the kinds of ploys and wiles that people will resort to when they need to gain advantage over someone else while still maintaining at least the appearance of British fairness. (It was pointed out to me on Twitter some years back by Lawrence Freedman that the geopolitical term brinkmanship, the art of advancing to the very brink of war but not engaging in it, was coined in the mid-1950s under the influence of Potter’s work.)

Potter had been a well-regarded English academic - he published on Coleridge and DH Lawrence, for example – and in a couple of Lifemanship books he turns his eye to the subject of book reviewing. He defines reviewmanship as “how to be one-up on the author without actually tampering with the text” – a quality that is readily discernable in plenty of book reviews one still reads today.

He offers, for example, a template for reviewing any specialist work of non-fiction.

Suppose the book is on a specialist’s subject like Rhododendron Hunting in the Andes. No known reviewerman will have been to the Andes; few will understand the meaning of the word ‘Rhododendron’. But only the novice will take refuge in vague praise, will speak of ‘the real contribution to our knowledge of the peaks in the Opeepopee district’ or ‘the debt we owe to Dr Preissberger, the author’. Much better to take the 'yes-but' approach, look up in any botanical manual the Latin name of any Rhododendron not listed in Preissberger’s index, and say, ‘Dr Preissberger leaves the problem of Azalea phipps-rowbothamii entirely unanswered.’ Or start, ‘It is surprising that so eminent a scholar as Dr Preissberger…’ and then let him have it.

He also includes some notes on ‘Reviewer’s basic’, which he credits to John Betjeman. (I don’t know enough about either man to know if there is an in-joke here.) The tenets of Reviewer’s basic include:

– any attack on the author under review is essentially friendly… Friendly attacks should begin with faint praise, but be careful not to use adjectives or phrases of which the publisher can make use in advertisements.

– To quote from a book no one else has read but you.

– To begin ‘Serious students will perhaps be puzzled…’

– To say, ‘In case there should be a Second Edition…’ Then note as many trivial misprints as you can find.

I think about Potter’s comments quite often, both when I read other people’s reviews or think about what to say – or what not to say – in my own. And this recent essay from Ann Kennedy Smith has prompted me to think about compiling my own list of dos and don’ts – and to think about the art of reviewing, if it is an art, more broadly.

Just for background, to those of you who only know me through my writing on Substack, I have reviewed for quite a wide range of magazines, newspapers and websites over the last few years, including The Economist, Engelsberg Ideas, History Today, Literary Review, The Quietus, The Spectator, The Telegraph, and The Times. Every title has its own way of working. (And indeed its own scale of payment. But we won’t get into that here.)

For me, usually, the process begins with a pitch: that’s how most of my reviews have been commissioned, although I’m always open to approaches, of course. Publishers issue catalogues of forthcoming titles twice yearly: January to June and July to December. These are mostly accessible on their websites, although for some reason they are usually hidden away in the online equivalent of a dark basement room behind a pile of boxes. I go through these and look for titles that I think look promising - either because of the subject or the author or, preferably, both – and that I think I might be competent to cover. (Obviously opinions may differ as to my actual competence, but that’s another matter.)

I also sometimes get sent advance proofs from the relevant publicity teams in the hope that I will review them somewhere. When that’s the case, I try to read at least a couple of chapters before I decide which to pitch. Sadly there simply isn’t enough time to read, let alone review, all the wonderful books that come across my desk. I feel endlessly guilty about that.

I then email the commissioning editors, trying to find a good fit between the book and the publication’s readership and commissioning strategies. It’s unusual for me to have read the whole of the book in question before I pitch the review, but I simply try to identify what seem to me the most interesting and compelling angles.

You’re always grateful, as a freelancer, for the editors who take the time and trouble to turn you down rather than leave you hanging. No doubt some editors receive vastly more cold pitches than others, which would make replying to every one unreasonably onerous, but the certainty of a rejection makes the freelance life a lot easier than the evanescent perhaps of an acceptance. For what it is worth, I suppose around one in four review pitches fail to land at all; equally I might not find a taker until the fourth or fifth editor. This part of the process is quite time consuming, not to mention morale sapping. Timing is tricky: as often as not, the review will have been commissioned out already by the time my pitch lands in the inbox.

We’ll come on to negative reviews later, but I would never knowingly pitch to review a book I thought was going to be bad. I have made mistakes along the way – but spending several days reading and writing about something I neither admire nor enjoy is not my idea of a good use of time.

Typically I pitch reviews around three months ahead of publication, although lead times do vary greatly. Most magazines, etc want reviews to appear a week or two before the book is published; some have rules about it. One editor commissioned me for the first time with four day’s notice to delivery: I read the book in two days and spent the other two working up the review. Some reviewers, of course, with high-profile books to cover that have to be read in top secrecy, have to turn around reviews in a matter of hours. I really don’t know how they do that.

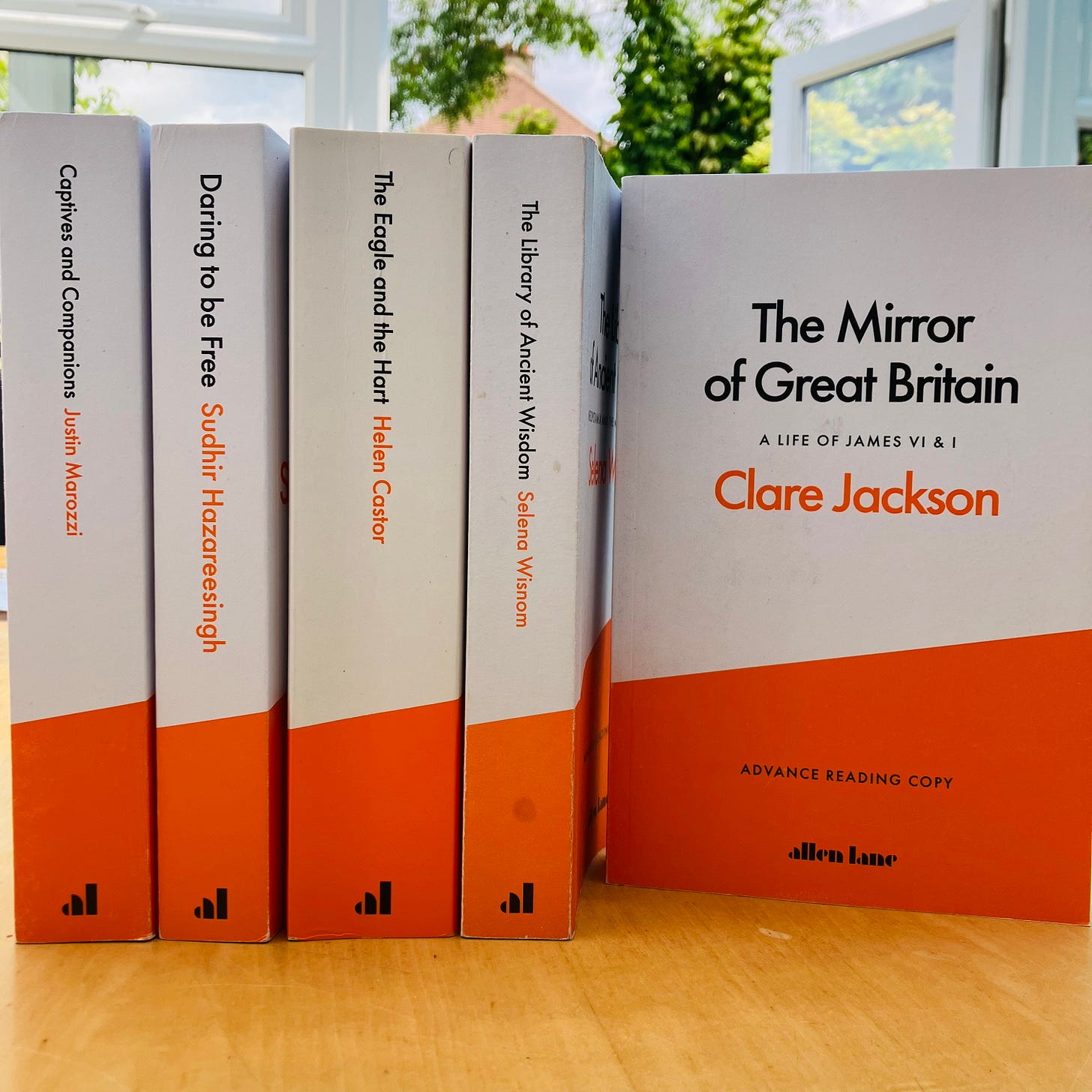

Review copies are typically what are called uncorrected proofs, from a late stage in the production process. These usually come as a properly bound paperback with a version of the finished design on the cover, although Penguin have a specific design for their proofs – see the image above – that references the classic Penguin colour scheme in a way that I think is incredibly stylish. It amazes me they don’t use the design for retail, because it is both delightful and striking. During lockdown, you were more likely to get sent a watermarked pdf, and some publishers – particularly academic publishers – still prefer to send out such pdfs to reviewers, a practice which I absolutely loathe because I hate reading books on screen. I’d probably refuse to review a book if I wasn’t sent a hard copy.

Having written your review based on an uncorrected proof, you have to check what you write against either a final print-ready pdf from the publisher, or a finished bound copy of the book itself. I can’t at this moment recall a situation in which a quote that I have wanted to use has changed, or been removed, but it does occur from time to time. (I’m reading a book right now which, in the proof, repeats the same sentence forty pages apart. The second instance has been rewritten in the final pdf.) I certainly wouldn’t want to submit a review that I hadn’t checked against the finished text.

Once your review is submitted, procedures vary. Sometimes you don’t see it again until it turns up in print. Some publications send you a proof to check. This might be a pdf of the laid-out page; this might be cut-and-pasted into the body of an email. Sometimes the editor will come back with queries or requests for clarification. Some editors are more interventionist than others – or perhaps sometimes I am more careless – but in my experience the editor will have unerringly identified places where my thinking is fuzzy, or where I have tried to condense things too much while trying to hit the word count. Other editors ask you to provide page references for every point you make in your review.

As for the process of reading for review, I know many reviewers like to write their thoughts in the margins of the proofs. I have done that a few times - when I’ve had to read a book while travelling, for example - but my usual practice is to sit and make notes longhand. There are typically more notes for the first half of the book than the second, since initially I am not sure what line I’m going to take and therefore not sure what information might be useful.

My notes fall into four broad categories:

– Quotes from the book that I think I might use. (Or sometimes quotes that I simply like.)

– Points that I might use, which I asterisk in the margin.

– Points that mark important narrative or thematic developments. (I have a terrible memory, so these also function as a roadmap through the book when I come to look back over my notes.)

– My evolving thoughts about the direction of the book, including any questions or theories I have about what the author is doing at any given point. These often develop into ongoing conversations with myself, cross-referencing back to notes on earlier pages.

But I suppose what I am really doing is asking myself what I am being told and why am I being told it. And, subsequent to that, what ideas animate the narrative or the argument. In all honesty, even though I have developed a loose set of marks and abbreviations to speed the process, I annotate far too much. Some books end up with fifty-plus A4 pages of notes, which is absurd – not least because it’s then difficult to navigate so much when I come to write the review. I end up annotating my own notes in different colour ink, usually red, cursing myself all the while for my stupidity and self-indulgence.

Some reviews you read give the impression of having been written alongside the reading of the book. Each paragraph will précis a chapter, for instance. There is nothing wrong with this as an approach, particularly if you are up against a deadline. It undoubtedly gives a good sense of what the book contains. But it’s not something that I like to do: I think I end up missing the forest for the trees. I find it easier to frame my thoughts about a book - and to decide which elements to feature in the review - only when I can consider it whole.

I use the Notes function on my phone as a kind of journal for all sorts of things, and at some point while I’m reading a book for review I’ll start forming my thoughts into sentences and paragraphs there, not all of which will make it to the actual draft, never mind the finished review. Quite a lot of these likely fall under Dr Johnson’s stricture about striking out passages of writing that one thinks particularly fine, but I find the process nonetheless helpful to think with. (Actually, I have experimented with used the Notes on my phone to do the whole note-taking process I outlined above, taking advantage of the OCR function on the phone’s camera for quotes and so on. It has its advantages – I don’t have to decipher my squirmy, scribbled handwriting, for one – but I’m not sure it’s any quicker or more practical in the long run.)

Now for the guidelines I try to operate under. I don’t know that any of these are particularly original – in fact, I am sure they are not – but they are the things that I try to do in order to produce what I think is a good review. You can judge for yourself how closely they proximate to Potter’s outline of reviewmanship above!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Broken Compass to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.